When Jimmy Carter served as president from 1977 to 1981, LGBTQ rights were barely on the political radar. Same-sex intimacy was still illegal in over two dozen states, gays and lesbians were barred from obtaining government security clearance, and the idea of gay marriage seemed like a distant dream. Political support for LGBTQ causes was largely taboo for politicians on both sides of the aisle.

However, Carter, a Southern Democrat and devout Baptist, stood out for his early support of pro-gay legislation and his willingness to engage with LGBTQ advocates.

Michael Bronski, a Harvard professor and author of A Queer History of the United States for Young People, noted, “The first federal or White House response to LGBTQ issues came under Carter, and for the mid-’70s, that was incredibly brave. It would have been just as easy for him to stay silent.”

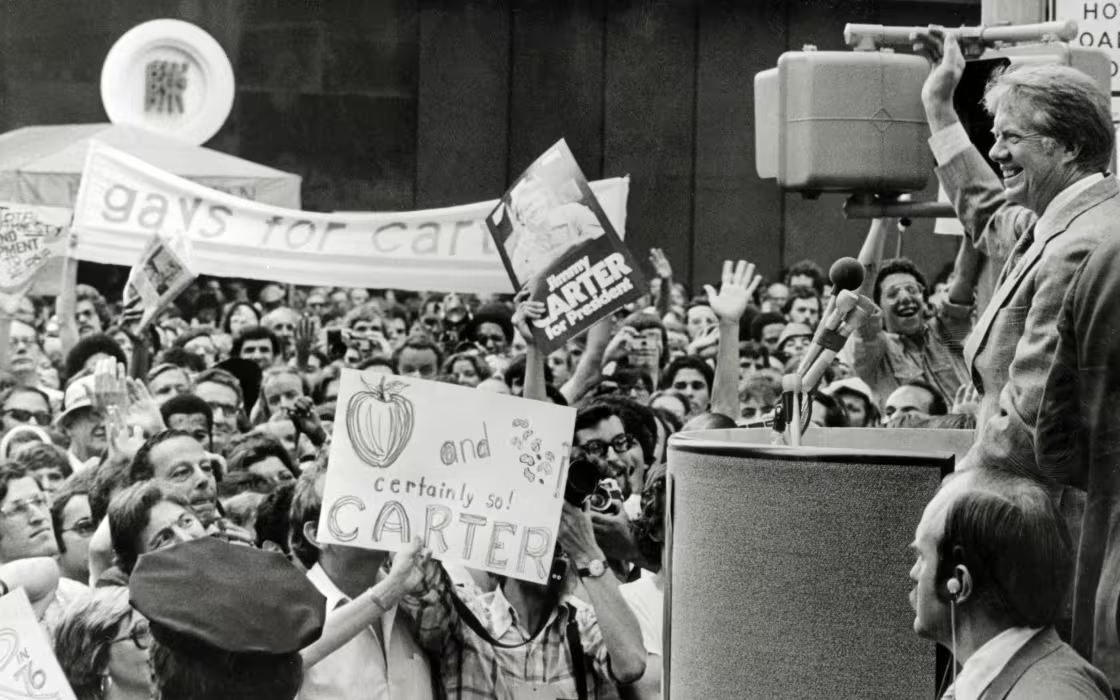

In 1976, during his presidential campaign, Carter, a former governor of Georgia, voiced support for the Equality Act, a proposal to amend the 1964 Civil Rights Act to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. While the bill was controversial at the time and remains divisive today, it laid the groundwork for future LGBTQ rights legislation. (An updated version, which also included gender identity, passed the House in 2021 but stalled in the Senate.)

When asked about the Equality Act at a news conference in May 1976, Carter responded, “I will certainly sign it, because I don’t think it’s right to single out homosexuals for special abuse or special harassment,” according to the National Archives.

A few days later, Carter’s team reaffirmed his position, issuing a statement that echoed his earlier comments on supporting anti-discrimination laws.

In March 1976, Carter told Philadelphia Gay News, “As President, I can assure you that all policies of the federal government would reflect this commitment,” according to a release available on the National Archives website.

Later that year, civil rights pioneer Harvey Milk endorsed Carter in a column for the Bay Area Reporter, praising him as “a man who believes that the government has no business in a person’s bedroom.” Milk, who would go on to become one of the nation’s first openly gay elected officials when he joined the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977, was tragically assassinated the following year.

Perhaps most notably, in 1977, a group of around two dozen activists from the National Gay Task Force met with presidential adviser Margaret “Midge” Costanza at the White House to discuss protections against discrimination. Historians view this meeting as a significant moment in the fight for LGBTQ rights.

James Kirchick, author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, highlighted that the 1977 White House meeting with gay activists was a groundbreaking event, marking the first time such a gathering took place at the White House. This meeting occurred just two years after the U.S. Civil Service Commission lifted its ban on gay people working in the federal government in 1975.

“Until that point, gay people could be barred from or purged from government jobs in large numbers,” Kirchick said. “So, having a meeting with gay rights leaders just two years later was significant. It symbolized the presidency’s endorsement of this issue and sent a message that gay people were citizens deserving recognition.”

However, Kirchick pointed out that while the meeting was symbolic, it didn’t produce tangible results. It took place while Carter was at Camp David, his presidential retreat in Maryland, suggesting that the administration, though allowing the meeting, considered it too controversial for the president to attend. “They did not want a photo-op with the president and these leaders,” Kirchick noted, explaining that the meeting was deliberately scheduled during Carter’s absence.

Despite this, the meeting was historic and stirred reactions from key anti-LGBTQ figures of the time. Anita Bryant, a former Miss Oklahoma and vocal anti-LGBTQ activist, criticized the meeting, claiming that it was a step toward legitimizing homosexuality. “What these people really want is the legal right to propose to our children that there is an acceptable alternate way of life,” she said, adding that homosexuality should not be seen as “not wrong or illegal.”

Michael Bronski, a historian and scholar of LGBTQ issues, pointed out that figures like Bryant, along with the growing influence of the religious right in the 1970s, made what would be a routine White House meeting today all the more significant at the time. “Carter was really sympathetic to gay rights,” Bronski said, noting that his actions helped establish a new national dialogue that countered the rise of conservative opposition.

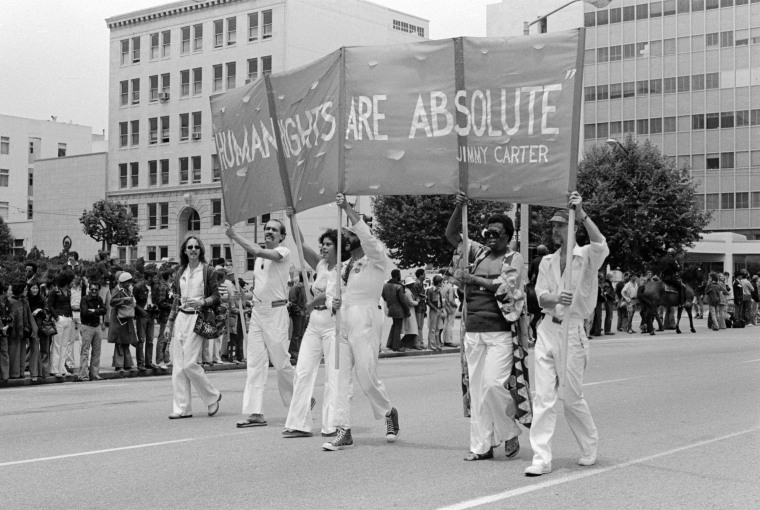

In 1978, Carter further aligned himself with the LGBTQ community by opposing California’s Proposition 6, also known as the Briggs Initiative, which sought to ban gay and lesbian individuals from teaching in public schools. At a rally in Sacramento, Carter declared, “As long as I am in the White House, our nation will always be identified as the nation that will insist and fight for basic human rights. I also want to ask everybody to vote against Proposition 6.” The measure was defeated by a margin of 58.4% to 41.6%, according to the GLBT Historical Society.

While historians acknowledge that Carter’s efforts on behalf of gay rights may seem modest by today’s standards, they believe he played a crucial role in setting the stage for future progress. “He may not have done as much as we wanted him to, or in the way we wanted, but he was the first to articulate policies around this issue,” Bronski explained. “He broke barriers, making it easier for future Democratic presidents to continue advocating for LGBTQ rights.”

Historians emphasize that Carter’s contributions to gay rights during his presidency must be viewed in the context of what followed — and what might have been achieved if he had been able to continue advancing progress, even if gradually, for gays and lesbians.

In 1980, Carter lost his re-election bid to Ronald Reagan, a Republican ally of the “Moral Majority,” just a year before the first official government report on AIDS was released. To this day, many activists blame the Reagan administration for its slow response to the growing AIDS crisis. When asked about the spread of AIDS in 1982, Reagan’s press secretary, Larry Speakes, famously laughed. It wasn’t until 1985 that Reagan publicly addressed AIDS, by which time an estimated 12,500 people had already died, according to the nonprofit group amfAR.

“If Carter had won and been in office when the AIDS crisis began, we would have seen a completely different federal response, and it likely would have saved hundreds of thousands of lives,” said Bronski.

Even after leaving the White House, Carter continued to speak out in support of gay people. In 2012, just months before President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, Carter became one of the most prominent Americans to publicly support same-sex marriage. Carter, who had taught Sunday school since the age of 18, used an unconventional argument to justify his stance: Christianity.

“Homosexuality was well-known in the ancient world, well before Christ was born, and Jesus never said a word about homosexuality,” Carter explained in an interview with HuffPost. “In all of his teachings, he never said that gay people should be condemned. I personally think it is very fine for gay people to be married in civil ceremonies.”

While Carter may not be the first figure that comes to mind for LGBTQ Americans when they think of equality, historians argue that his legacy on LGBTQ rights was more significant and courageous than he has often been credited for.