Reported by CNN

China has built or expanded over 200 specialized detention centers as part of Xi Jinping’s growing anti-corruption campaign, targeting a broader range of public sectors beyond just the Communist Party. Since taking power in 2012, Xi has ruthlessly pursued corruption and disloyalty, dismantling rivals and consolidating control over the party and military. Now, in his third term, this crackdown has become a permanent feature of his rule, with the system of “liuzhi” — a detention regime that holds suspects in padded cells with 24/7 surveillance for up to six months, without access to lawyers or family. This expanded purge now impacts not only party officials but also private entrepreneurs and administrators in schools and hospitals.

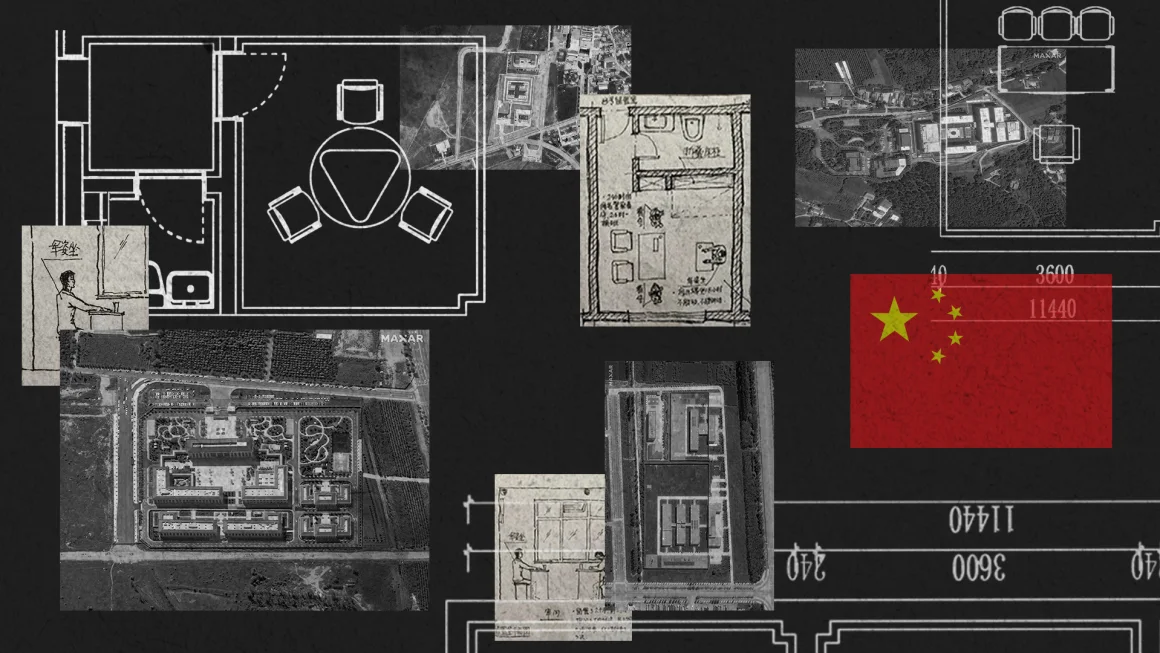

For decades, the Communist Party’s disciplinary body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), operated a secretive and extralegal detention system to interrogate officials suspected of corruption and misconduct. Under investigation, party members were often taken to hidden locations, like party compounds or hotels, where they were held for months without access to lawyers or family. In 2018, amid growing criticism of widespread abuse, torture, and forced confessions, Xi Jinping abolished the controversial practice known as “shuanggui” (or “double designation”), which allowed the party to summon members for investigation at designated times and places.

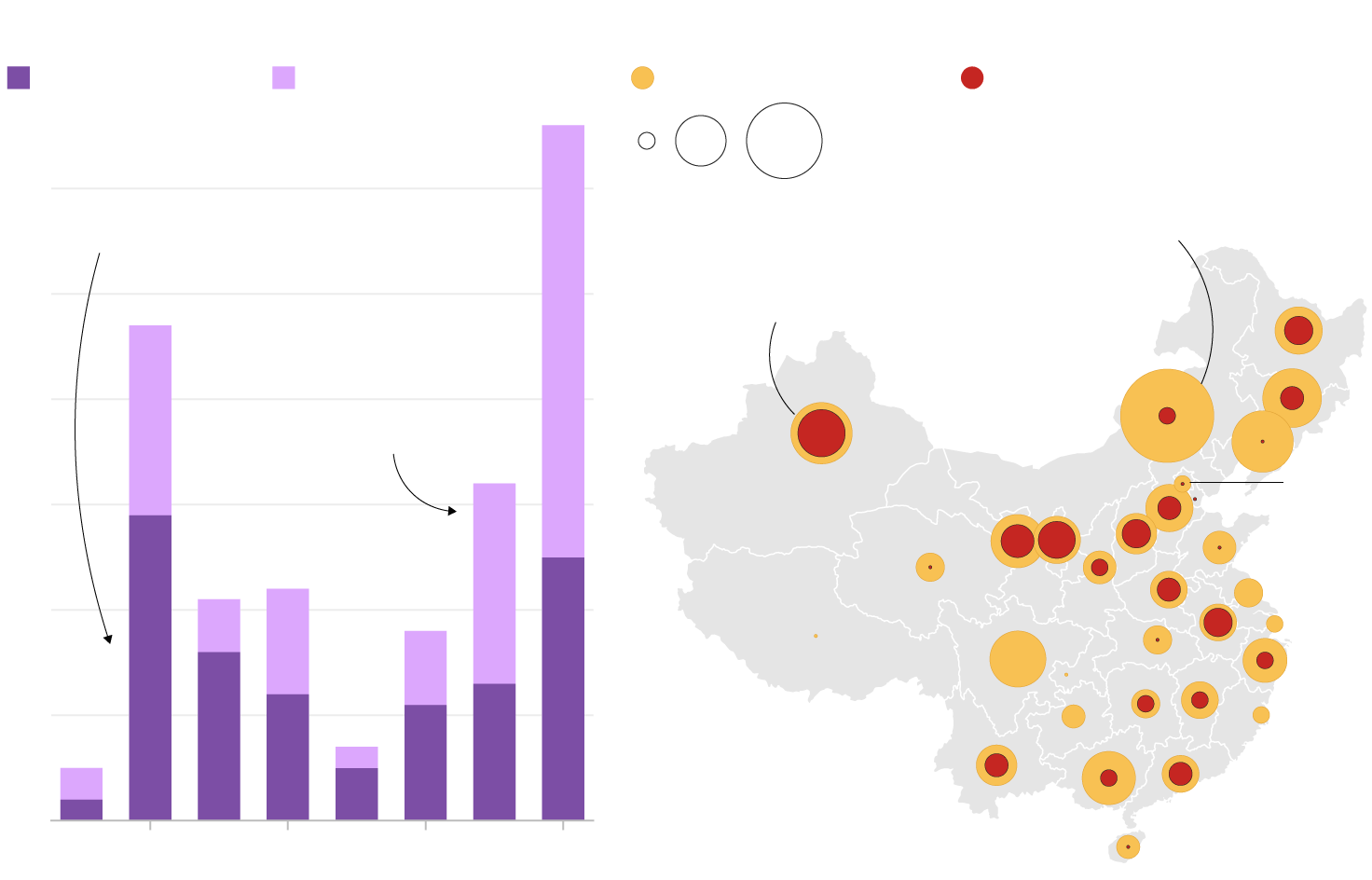

CNN has uncovered over 200 detention center construction projects across China.

Although Xi Jinping abolished the controversial “shuanggui” system, which allowed secret detentions of Communist Party members, he did not eliminate secret detention altogether. Instead, he legalized and expanded it under a new name, “liuzhi,” and placed it under the authority of the National Supervisory Commission (NSC), a powerful agency formed in 2018. The NSC consolidated the government’s anti-corruption efforts and merged them with the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), creating a unified force that oversees both the party and the public sector.

The liuzhi system retains many of the same features as its predecessor, including holding suspects incommunicado with no independent oversight. A criminal defense lawyer who has represented officials in corruption cases told CNN that detainees still face abuse, threats, and forced confessions under liuzhi, with few protections for their rights.

Liuzhi casts a broader net than shuanggui, targeting not only party members but also anyone in positions of public power, such as civil servants, managers of schools, hospitals, and state-owned companies, as well as businessmen involved in corruption. High-profile detainees include billionaire Bao Fan and former soccer star Li Tie, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for corruption.

At least 127 senior executives from publicly listed companies, many of them private businesses, have been detained under liuzhi, with the majority of detentions occurring in the last two years. State media claims the expanded jurisdiction addresses gaps in the anti-corruption fight, tackling abuse of power across the public sector, from bribery in hospitals to mismanagement in schools.

Critics argue that the system reflects Xi’s growing authoritarian control, further tightening the party’s grip on Chinese society.

Between 2017, when China launched local supervisory commissions as pilot programs before establishing the National Supervisory Commission (NSC), and November 2024, at least 218 liuzhi centers have been built, renovated, or expanded across China, according to CNN’s review of publicly available government documents and tender notices. The actual number is likely higher, as many local governments do not post tender notices online or remove them after bidding concludes.

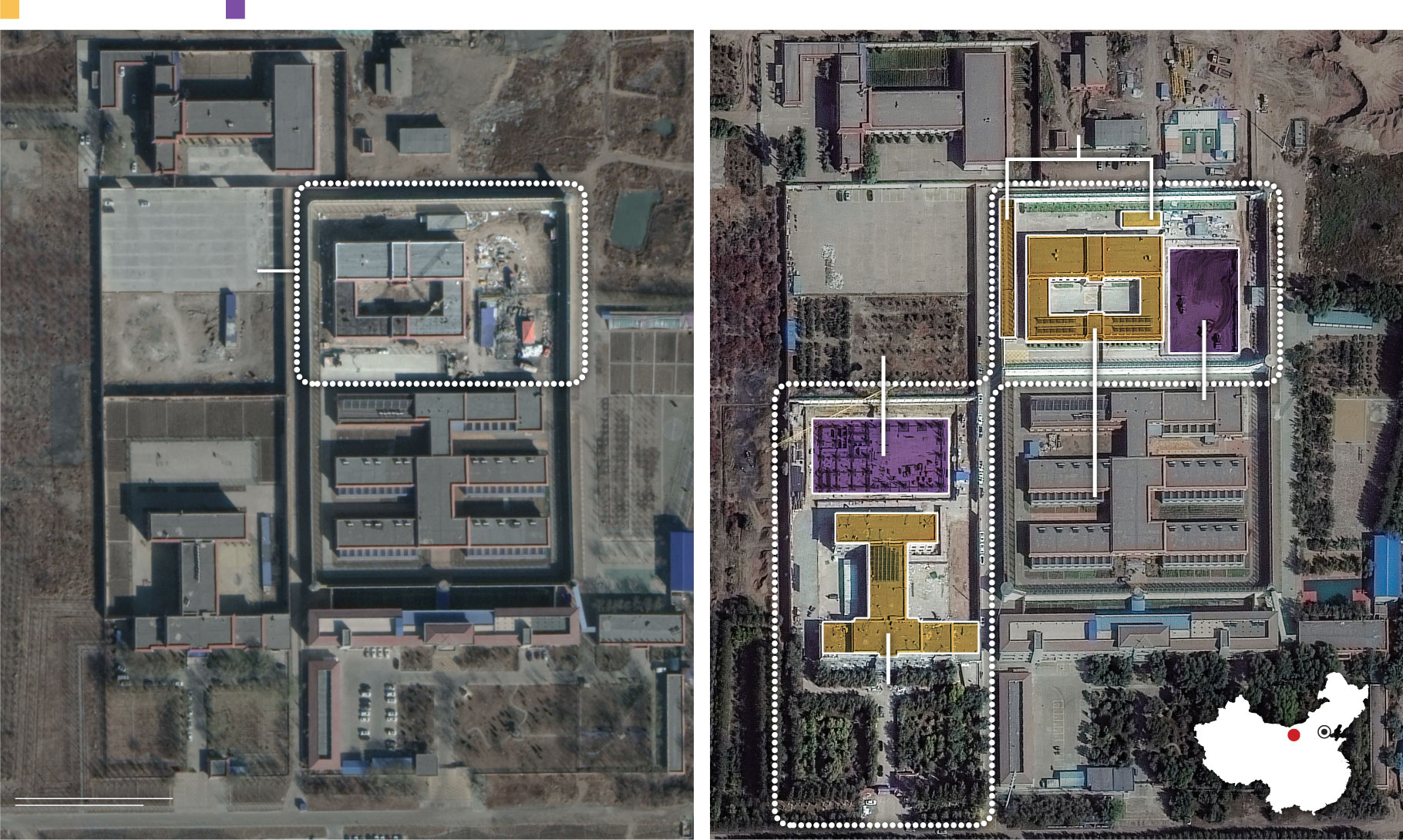

The construction surge is largely driven by increased demand for detention facilities due to the NSC’s expanded authority, as well as efforts to standardize and regulate liuzhi centers, replacing the hotels and villas often used for the previous “shuanggui” system, the documents show.

CNN has reached out to the National Supervisory Commission and the State Council Information Office, which handles press inquiries for the Chinese government, for comment.

Soft padded rooms

An analysis of tender notices shows a slowdown in construction during the pandemic, but the number of projects surged again in 2023 and 2024. More detention centers have been built, with increased funding allocated to provinces and regions with higher ethnic minority populations.

In Shizuishan, a city in the northwestern Ningxia region, home to the Hui Muslim minority, a 77,000-square-foot liuzhi facility was approved for construction in 2018, with a budget of 20 million yuan ($2.8 million), according to a government notice.

The document offers a rare insight into the design of detention centers. All cells, interrogation rooms, and the infirmary must have fully padded walls, rounded furniture with no exposed edges, and anti-slip floors. Electrical wiring and power sockets are prohibited, while ceiling-mounted installations, such as cameras, lights, fans, and speakers, must feature “anti-hanging designs.” Bathrooms require padded washbasins and stainless-steel toilets, with showerheads and cameras mounted on the ceiling, according to the guidelines.

These enhanced safety measures aim to prevent detainees from self-harming, a problem that plagued shuanggui detentions in the past.

However, Shizuishan’s liuzhi center proved too small to handle the growing number of detainees. In June, the city announced plans to expand the facility, citing “insufficient facilities and equipment.” The expansion includes a new interrogation building, a staff canteen, and the reconfiguration of existing structures to create additional detention cells.

While official figures on shuanggui detentions were never published, data on liuzhi is similarly scarce. In 2023, national figures showed that 26,000 people were detained by the NSC and its local branches across China.

Provincial data, though incomplete, reveals a sharp increase in detentions. In Inner Mongolia, 17 times more people were placed under liuzhi custody in 2018 compared to those detained under shuanggui in 2017, according to the region’s supervisory commission.