When Syrian rebel leader Ahmed al-Sharaa stood in Damascus to deliver a victory speech after a rapid campaign that brought down Bashar al-Assad’s regime, one comment slipped under the radar. Amid declarations of triumph, he mentioned an illicit drug that had quietly become a scourge across the Middle East over the past decade.

“Syria has become the biggest producer of Captagon on earth,” he said. “And today, Syria will be cleansed, by the grace of God.”

Captagon, a powerful amphetamine-like pill often dubbed the “poor man’s cocaine,” remains relatively unknown outside the Middle East. But within the region, it has fueled addiction crises, smuggling operations, and violence. Syria’s shattered economy—devastated by years of war, sanctions, and mass displacement—became fertile ground for the production of this highly addictive narcotic.

Neighboring countries have struggled to stem the tide of pills flowing across their borders. The World Bank estimates the annual trade in Captagon originating from Syria to be worth a staggering $5.6 billion (£4.5 billion).

The scale of the operation suggested it was more than just a criminal enterprise. Many suspected the Syrian regime itself had orchestrated the industry, using it as a financial lifeline amid international isolation.

Weeks after al-Shara’s speech, newly uncovered evidence appears to confirm these suspicions. Striking images and revelations have emerged, painting a clearer picture of how Captagon production became intertwined with state power under Assad’s rule.

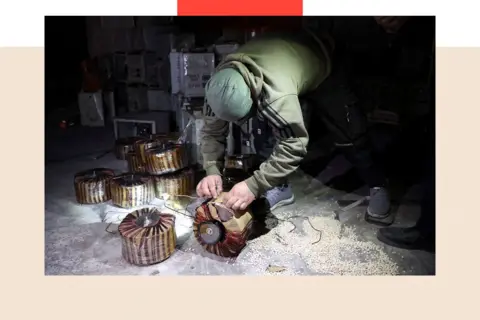

Videos circulating online, reportedly filmed by Syrians raiding properties tied to relatives of Bashar al-Assad, reveal rooms packed with Captagon pills being manufactured and packaged, often concealed within fake industrial products.

Other footage shows stacks of the pills discovered at what appears to be a Syrian military airbase, set ablaze by rebel forces.

During a year-long investigation into Captagon for a BBC World Service documentary, I uncovered how this drug has become a fixture of life across the Middle East. In wealthy Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia, it’s a party drug for the elite. In countries like Jordan, it devastates working-class communities.

“I was 19 when I started taking Captagon, and my life unraveled,” Yasser, a young man in rehab in Amman, Jordan, told me. “I stopped eating, my body broke down, and I was hanging around people who lived for this stuff.”

As rebel leader Ahmed al-Sharaa and his group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), now face the challenge of rebuilding Syria, they must grapple with the widespread Captagon addiction that grips the region. Without access to the drug, many addicts could face withdrawal crises.

Caroline Rose, a researcher specializing in Syrian drug trafficking at the New Lines Institute, warns of potential pitfalls. “My concern is they’ll focus solely on cutting supply, ignoring the need for demand reduction and treatment programs,” she explains.

Beyond the addiction crisis lies another critical question: how will Syria’s fragile economy, which relied heavily on the £4.5 billion Captagon trade, adapt to its loss? And as the old regime’s smuggling networks are dismantled, how will al-Sharaa prevent other criminal groups from stepping in to fill the void?

The Middle East’s War on Narcotics

The rise of Captagon has plunged the Middle East into a full-blown narco-war.

While documenting the crisis with the Jordanian army along their desert border with Syria, we witnessed the fortified fences and heard harrowing accounts of soldiers who lost their lives in shootouts with Captagon smugglers. Jordanian officials accused Syrian forces on the other side of the border of actively aiding the traffickers.

The drug trade has alarmed nations across the region.

At one point, Saudi Arabia halted imports of fruit and vegetables from Lebanon after authorities repeatedly intercepted shipments of produce, such as pomegranates, hollowed out and stuffed with Captagon pills.

We filmed in five countries, including both regime-controlled and rebel-held areas of Syria. Through consultations with key sources and access to confidential court records from Germany and Lebanon, we uncovered significant details. We identified two major parties deeply involved in the trade: Assad’s extended family and the Syrian armed forces, specifically the Fourth Division, led by Assad’s brother, Maher.

Questions regarding Assad’s brother